Summary:

- Learn how to mitigate product failure before it happens with powerful techniques like Assumption Mapping to ensure project success.

- Reducing the chance of product failure can be accomplished by surfacing and mitigating assumptions, risks, and fears before starting development. The alternative is hope-based management, aka gambling.

- One method for surfacing concerns is Assumption Mapping, a group exercise that categorizes and prioritizes assumptions about what is being built, who it is being built for, and how you will make a profit.

- The most significant assumptions should be tested via the minimal viable experiments to de-risk the project.

- The process can also surface indicators for project tracking.

Parable:

Wizzy owned a successful farm supply store. He had a large extensive rebate program that had helped made Wizzy’s Farm Store successful. Each farmer got a discount from the store if they put a sign in their field near the road saying they grew crops using Wizzy products. This was a boon for Wizzy as the signs went up, and more people came to his store, even if they weren’t farmers, to buy products for plant cultivation.

The downside was Wizzy had a mountain of complex contracts. Each farmer had a unique contract with Wizzy, creating a week’s worth of work every month to get the checks out. This process was owned by Wizzy’s wife. She was not pleased and told him recently that this was the last time she would fool with figuring all those rebates out. She told him just make it a single 15% discount, which was the average of the rebates.

Wizzy, having a key stakeholder unhappy, immediately set to work but was worried about upsetting his longtime customers. Luckily three of the farmers were in the store when his wife made her ultimatum. He went to each and asked if they would be okay with a 15% rebate if it meant they would get their money back faster. They all agreed.

At the end of the month, Wizzy sent out an email to his 87 rebate customers, notifying them of the change. Wizzy received 45 outraged responses, including 5 of his largest customers indicating that not only would they take down their signs immediately, but they would buy from Andy’s Mega Discounts instead.

The customers that were happy and stayed were the ones that saw an increase in their rebate checks, but they had the smallest farms and bought the least. Those that got their rebates cut were larger farmers or the ones nearest the main highway. Sales volume and market awareness took a huge hit, and Wizzy started losing money. Wizzy eventually went out of business, and his wife left him for the now ultra-wealthy Andy.

Mitigating failure before it happens

As I have discussed in previous articles, many products fail, and if you work long enough in product delivery, you too have had products fail. The failures are usually rooted in the desirability of a product by the customer. This could be because they already had another better solution, but sometimes it was because you couldn’t make it at the right price or you couldn’t make it at all. How could you have seen this before? What about the project/product you are working on right now, will it fail? What has you worried?

It could be because we don’t see failure because of hubris (aka ego), or we are worrying about it but not addressing the fear with ourselves or others. Without admitting and specifying our concerns about the unknown, we cannot hope to overcome them. These things may be an issue, or they may not be, but if we don’t address them we assume everything is okay. Inaction to examine our ego and fear is a decision. This decision is what I call hope-based project management (HBPM), where we hope things work out, and if we are lucky, they do, but just like a casino, luck doesn’t last forever.

There are methods for examining risks, unspoken concerns, and assumptions. My favorite technique is Assumption Mapping, which I will outline below. When I bring this process up to some project teams, people argue, “Why are we wasting our time. We can’t stay in analysis forever”. They are partially correct, we don’t want to get stuck in what is called “analysis paralysis,” which I usually call “analysis paralysis cowardice” (APC). To move through the APC phase safely and effectively, we need to prioritize our analysis so that we have time to de-risk those things that will impact us the most by not knowing but not wasting our time nitpicking.

Categories of Failure

As an alternative to HBPM and APC, we need to remove ambiguity by visualizing, figuring out what is essential, prioritizing, validating, and mitigating our assumptions, or for short, Assumption Mapping.

To do Assumption Mapping, we first need to look at the assumptions that could lead to failure in our project. These broad categories help us group assumptions, and different kinds of assumptions need different techniques/tests to de-risk them. For the Assumption Mapping exercise, there are three categories of assumptions:

Feasibility – Can we build it

Desirability – Who/Why does someone want it

Viability – How can we make money if we build it.

These three categories are not mutually exclusive, meaning one affects the other. A customer may desire free beer, but the viability of supplying the beer is probably zero. It may be feasible to create dinosaurs from DNA from insects locked in amber, but their occasionally eating a guest may impact the overall desirability of coming to Jurassic Park.

Because of the interplay of these categories, the types of risk come out when discussing them with a cross-disciplinary group before you go to all the expenses of buying an island off the coast of Costa Rica, setting up over 50 miles of electrified perimeter fence, and hiring a single developer with money problems to build your entire automation system. Some of these problems could have been mitigated using Agile development methodologies like pair programming and stakeholder reviews.

Think about how different Jurassic Park would have been had they done some Assumption Mapping sessions up front to talk about the risks. If they tested them by, say, reproducing a single dinosaur and seeing how that went? Hammond was a master of big-release hope-base management.

These categories help us indicate who should be showing up in an Assumption Mapping session. You need users or user experience people (desirability), finance people (viability), and delivery team members (feasibility). You may add additional representatives based on your business and concerns; perhaps you are concerned with liability and need to invite lawyers. For feasibility, consider including manufacturing, support organizations, or DNA scientists.

Assumption Mapping

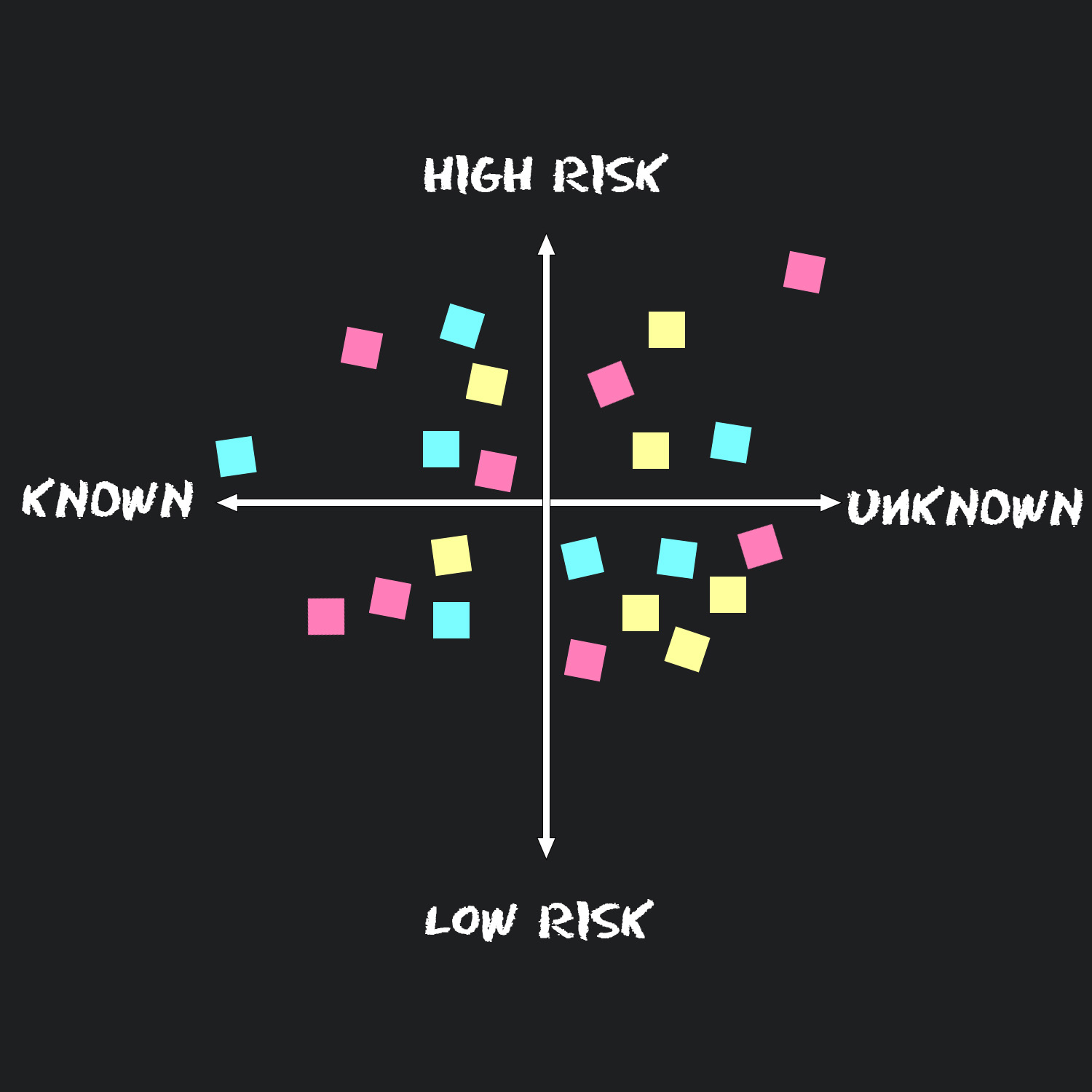

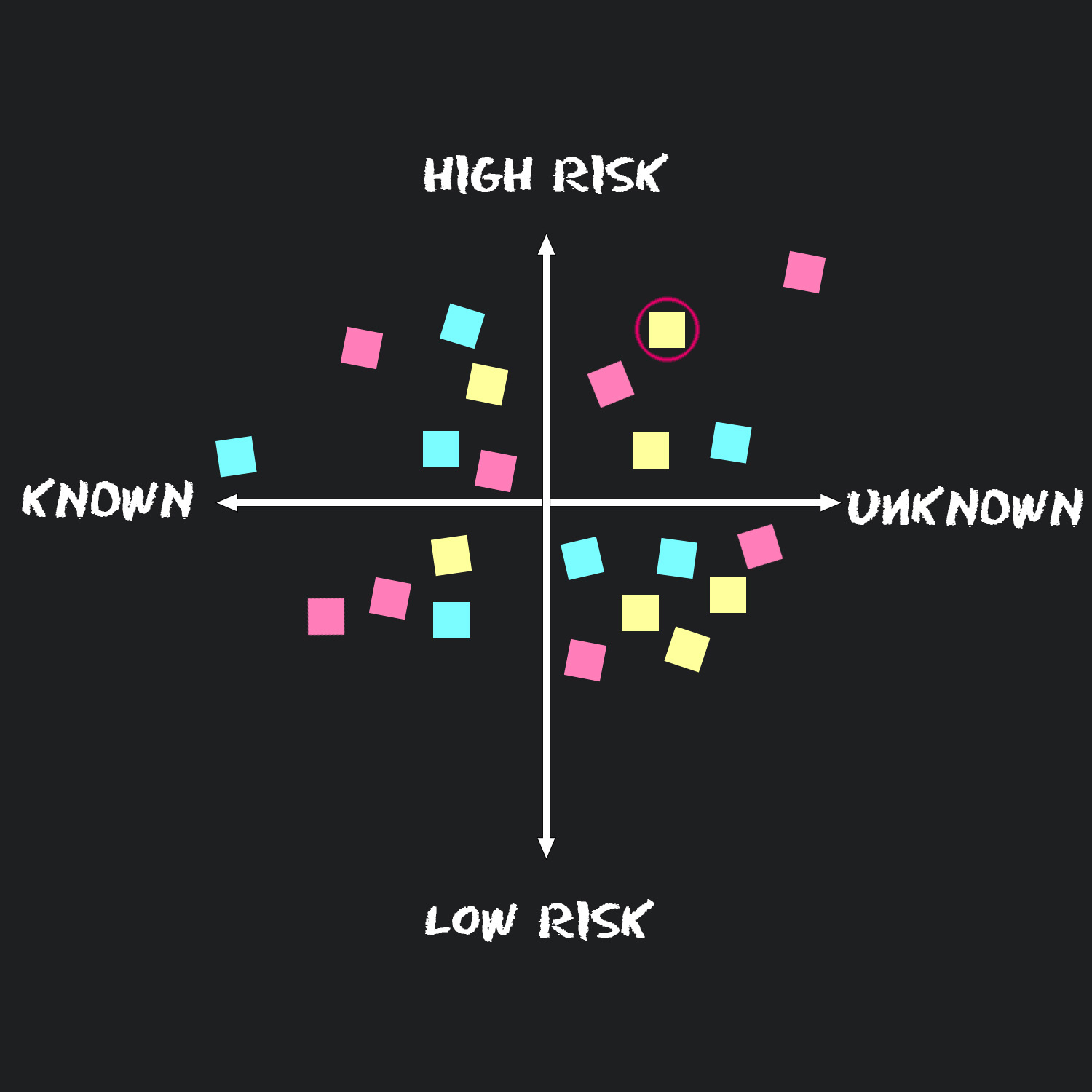

Now that we understand the people and categories let’s discuss the process. Our goal is to surface our most significant assumptions and the risk associated with them. As a group, each person will:

- Write down your assumptions on a sticky note with a color that matches the category.

- The author of the note will categorize and prioritize it by placing it on a board like the one below.

- Discuss the assumption and see if it is in the correct quadrant.

- At the end of the meeting, you will have an assumption board that looks like the one below.

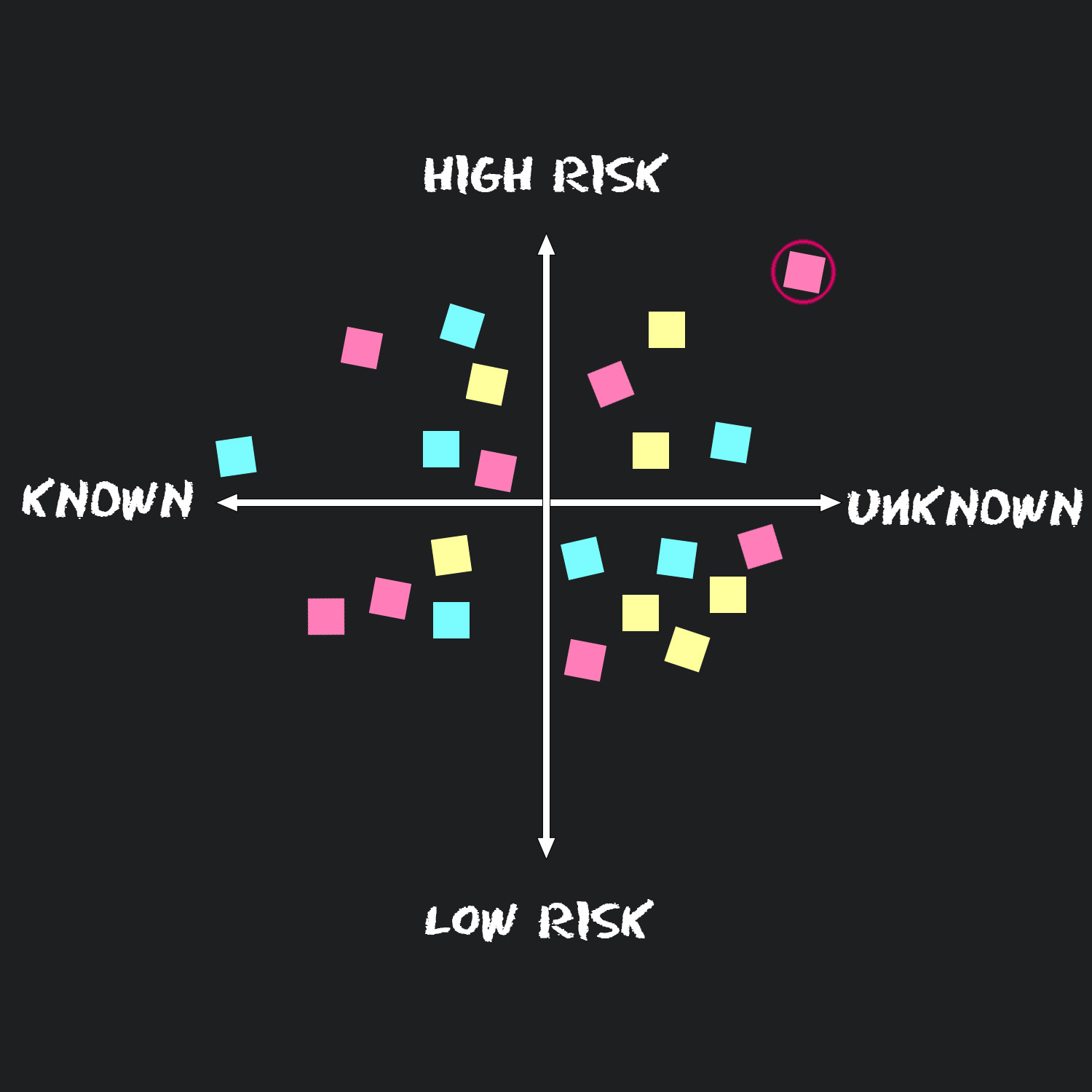

- Everything in the top right quadrant should be de-risked outside the Assumption Mapping meeting.

What discussion looks like

Assumption:

The first is a feasibility assumption:

Website that looks good on any phone

Things to consider:

But who put it there? Was it the delivery team member or a finance person? What kind of phone, eveny a flip phone?

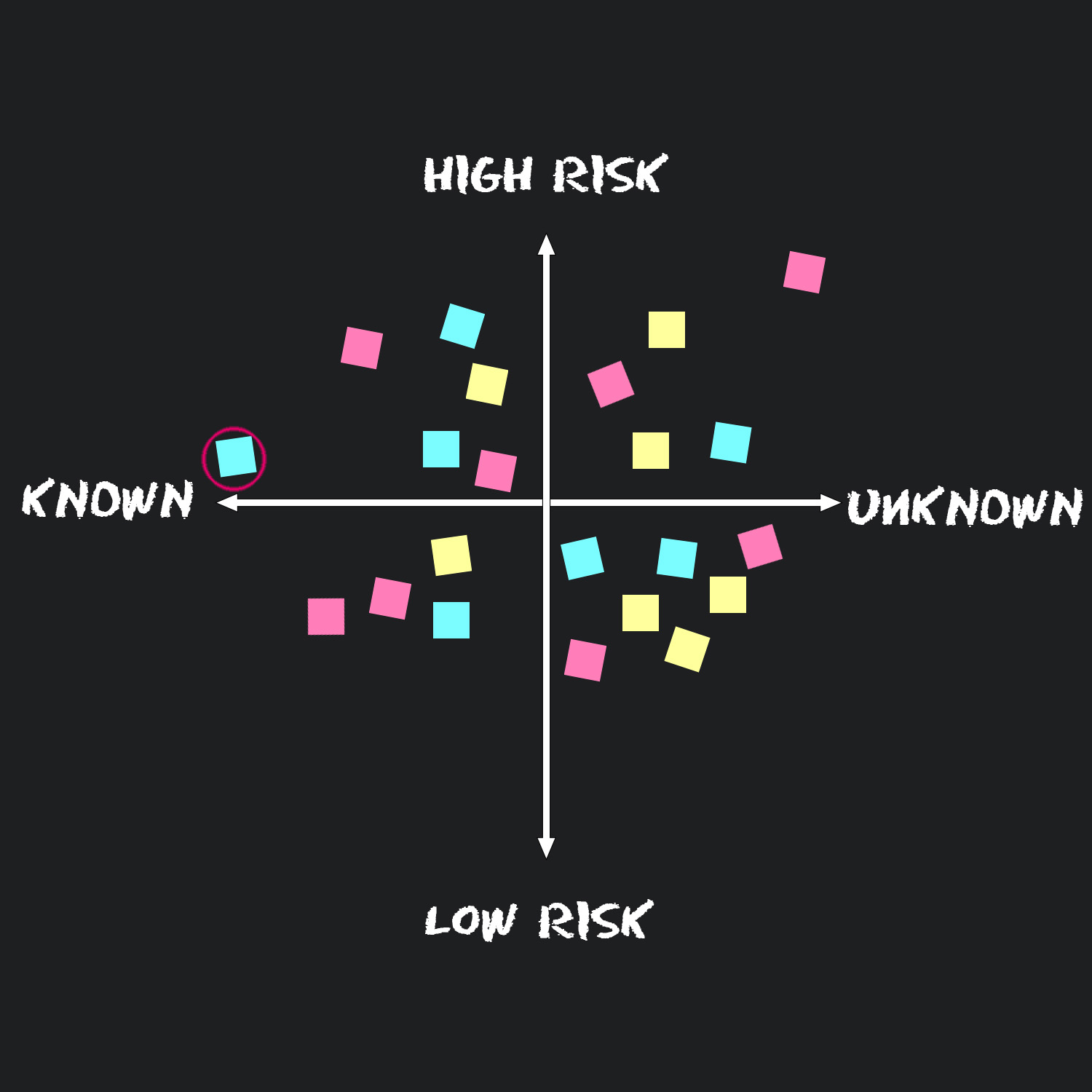

This is where someone on the delivery team could pick that sticky up and move it over to the unknown high-risk category if they need help making a mobile website. The conversation around feasibility assumptions can de-risk the delivery and help set expectations with the group on what is needed. In this case, maybe training or a contractor will come in and uplevel the team’s skills.

Real-world example:

One of the most powerful examples of this was when I had a senior architect stand up, pick up a feasibility note that was in the bottom left quadrant, and jump to put it in the top right quadrant. The room was hushed. He turned and said, “We don’t have a product that can do anything like this. Even if we did, a security review would take at least a month.” It was clear many other assumptions then needed to change, including design and timelines.

Assumption:

In this example let’s look at a desirability sticky note that says,

The user hates our current website

Things to consider:

How do we know that? What do you mean by hate? Which users, all of them or only some?

Answering these questions may be difficult during the mapping session but collecting them and testing them to see if that is true. This can be done through customer interviews, mockups, and collecting data from website analytics.

Here we want to make sure our customers have a problem. What is it, and how will we know we have solved it? One of the more common unwritten assumptions is we know what “good” looks like. It is worth noting that Wizzy did ask some customers but didn’t ask enough. One of the most significant desirability assumptions is assuming you know who your customer is.

Real-world example:

One of the scariest examples I’ve seen of this was when I was facilitating an Assumption Mapping session for a large program. The engineers made an assumption, “Our customer is anyone.” The following conversation occurred:

Me: Oh, so I would want to buy this?

Engineer: No, not an individual but a business.

Me: So if I owned a restaurant, I would want to buy it?

Engineer: No, no, like a large huge business.

Me: Okay, so if I work for Walmart Corp. I would want to buy one?

Engineer: Definitely!

Me: As a Walmart employee, what problem would I want to solve with this?

Engineer: … Okay, maybe not Walmart… but maybe… like a University doing research.

Me: Okay, as a university, what research problems do I have today that can’t be solved without this product?

Engineer: … Big ones.

Me: Which ones?

Engineer: The biggest.

The engineers developed an interesting product, but there wasn’t a market for it. In that conversation, the total available market and who we needed to sell to changed three times. All of which were huge impacts on the viability of the product. Needless to say, that product failed, but not before they ignored the outcome of the meeting and wasted several million dollars. It is essential before you start facilitating one of these Assumption Mapping sessions to ask, “Will you change what you are doing based on what we discover today, up to and including canceling the project?” If the answer is no, you should probably do something else with your time.

Assumption:

Lastly, an example of viability. This sticky note says

Increased sales if customers love our website.

Things to consider:

This could be considered a desirability risk. The key here is it may be both, but for this sticky, the writer wanted to raise the financial risk. How much increase can we expect? How are we measuring sales today, and do we do it by website usage? What would the increase need to be to warrant a change in our product?

These questions may require financial analysis, one such method I outlined in my previous article here. To answer these risks, we need to build features to instrument sales as a function of website usage. At its core, any product we build is to solve a problem for someone in exchange for money greater than the cost it took to build it. This can be measured in various ways in the form of time savings, ads seen, direct sales, etc. The key is we need to measure it, and we need to set the bar early. If the economic bar looks too high, we may want to try some less risky bets.

Real-world example:

I was working with a team trying to overhaul some data storage and access used for analytics. A viability note said, “We will create better decisions with clean data.”

Me: Are you making bad decisions now?

Them: No… just not optimal ones.

Me: How do you know they aren’t optimal?

Them: Because we take a long time to get data.

Me: You making okay decisions it just takes longer than it should?

Them: No, the decisions would be faster and better with clean data.

Me: So the data that takes a long time to get isn’t good either?

Them: Right.

Me: When you finish this project, will you be able to show the old decision vs. the new one and measure better?

Them: <staring at me blankly>…

In some projects, there is an assumption if we implement new software, update our framework to the new thing, or switch to the new trendy vendor, things will be better. But better how? How are you showing this?

This could be a multi-million dollar savings, I am certainly a fan of clean data, but the magnitude of the problem could be thousands or billions of dollars. In each case, you may prioritize differently. Without this, you prioritize “cleaner”, “better”, “newer”, etc. Using ambiguous viability to prioritize results in prioritization based on charisma and organization intimidation.

In Wizzy’s case, he was doing something to appease his key stakeholder regardless of the cost. We shouldn’t change our business without understanding the financial impact of doing so.

Other questions to ask to help facilitate Assumption mapping:

Feasibility

- Our biggest technical problem is what?

- We can do this uniquely better than others because?

- Our biggest security/legal risk is?

- How can we support what we have built?

- How will we measure done?

Desirability

- Who are our users?

- What problem do we think they have?

- Why can’t they solve this problem today?

- Do they have a bigger problem than this one?

- How will measure to know we have solved it?

Viability

- Our customers will make money by?

- Our customers will save time by?

- If we are late, what is the financial impact? What is late?

- We will measure income by?

The outcome of the exercise

When you leave the meeting, you should know your unknown high risks visualized and agreed to by the team . Then it is the responsibility of the product owner or project manager to make sure the most significant risks are owned by someone in the room to get them out of that category. Here are some possible tests for each category. It is essential that the testing isn’t a whole project in and of itself. Create a minimal viable experiment that will either reduce the risk or make it more known, ideally both. This can be as small as asking a question or as big as a prototype, the test should be proportional to the risk being mitigated.

Feasibility

- A small proof of concept.

- Conversation for our security/legal team.

- Architecture and estimation sessions with the delivery team

Desirability

- User research

- Customer Interview

- Mock-up of a possible solution, pictures, not final products.

- Prototype

- Analytics analysis from our current products

Viability

- Market analysis

- Monte Carlo Simulator ala Douglas Hubbard’s How to Measure Anything.

- Customer conversion analysis in conjunction with the prototypes.

For each category, it is crucial to identify measurements that indicate success because we want to remove the ambiguity of what “done” looks like. Usually, you will want to find some leading indicators, as most financial indicators tend to lag behind the work you are doing. In that regard, ensure a way to generate the data to create your measurement as part of the project. There is a lot more that could be discussed around key performance indicators (KPIs). Still, for now, I only leave an assumption mapping exercise when I have some measurements for each category.

Final Thoughts

When developing projects, we frequently focus on what is being built. Is it built on time, on budget, and specification? Unfortunately, this is, at best, a measure of our output, aka our feasibility. The most important thing to our success is as we know the user’s desirability, which is the outcome of our project. Once we release something, we want to know the financial impact of what we delivered, which is the after-the-fact analysis of our viability.

How many projects have you been a part of where the only focus was output? Once a project was completed, even if the product was built well, did it sell? Did the company make money? Was it even used?

In our first example, Wizzy could change his rebate system on time and notify all his customers. The feasibility was never Wizzy’s most significant risk in the change. He needed to test and measure customer desire and financial impacts. Most programs only track the least essential risk, the output of the delivery team status.

What if Wizzy asked more of his customers? What if Wizzy had seen the financial impact of his most important customers and ensured he asked them first instead of the ones available to him? How we test our assumptions and change our behaviors based on the answers is as important as what we deliver.

Leave a comment