Summary:

- Accountability is critical when making decisions that impact others. To be accountable, we must feel we have something to lose if we are wrong. The decision makers’ loss should be aligned and proportional to those impacted by their decisions.

- Nassim Taleb’s book “Skin in the Game” illustrates this way of thinking and shows how important it is for understanding how the world works.

- Applying this thinking framework to various software development and business aspects will create higher-quality and higher-value outcomes.

When people make decisions that impact others, what can drive them to make the best decision for the group/organization? Many decision processes can help us focus on what matters, minimize bias, and make an educated decision with as much input from experts as possible. One method I like has been outlined in an article here. We don’t have the time to make a robust model for many decisions. This means a hundred tiny decisions that affect our organizations happen without rigor. Further, we can’t entirely remove some biases even when implementing decision-making models.

In a recent article, I discussed the misuse and misunderstanding of accountability. I want to discuss where accountability matters, especially when we need to be accountable to others, like peers, partners, and shareholders.

The best way to have accountability is to have an alignment of the decision maker’s self-interest and those interested in that decision. Nassim Taleb’s book Skin in the Game explores this operating mode, not just a theoretical exploration of risk, stickiness of ideas, uncertainty, and accountability. It is challenging us to rethink our decision-making processes. The book argues that individuals and institutions should have ‘skin in the game’ when it comes to decision-making, meaning that they should have something to lose if their decisions are wrong. Taleb’s insights are not confined to politics and economics; they are equally applicable to the software industry, where the consequences of bad choices can be significant.

Here, I want to apply his insights to enterprise software, where people sometimes make decisions without skin in the game. As a result, the code and value generated are negatively impacted.

Software development and Reuse

In many organizations, the group that develops or configures the software differs from the group that supports it. The operations group creates a series of gates and hurdles to try to slow software developers down and ensure the quality of the code because once they accept it, they own whatever it does. The operations (ops) organization will support it, not the group that created it.

This slowdown and lack of skin in the game delay releases and usually results in lower-quality code. However, if the group that creates the code is waking up in the middle of the night, they are far more likely to test their code and ensure it doesn’t happen. They have a personal interest and an interest in sleep that will motivate them to create the highest-quality code they can produce. This combination of development, deployment, and support roles is sometimes called a DevOps organization. I like to say, “If you Dev it, you Ops it.”

This is true whenever ownership is split across roles, and there is a chance to point fingers. By consolidating “blame” to the person doing the work, that is clear ownership and accountability. In the past, I’ve been a part of an organization where people would make huge solutions, hand them off to separate support organizations, and then no one would maintain them. The support organization would keep it alive for a few years until software solution drift occurred. This occurs when a solution drifts away from the business need and the technical landscape to support it. Much like a boat without an anchor, the solution drifts away and cannot be used.

In an organization like this, reusable services and capabilities are rare. No one trusts the boat drifting out to sea. Just like software developers don’t trust open-source software without recent contributions, a piece of software without a team is a dangerous thing to depend on.

Leaders

Last year, Forbes published an article noting that most CIOs don’t stay at a given company for more than 3 to 5 years. This isn’t limited to the CIO; executive tenure is shrinking for many C-suite positions (e.g., CEOs and CMOs). Most executive decisions take several years to determine if they were successful. How can there be any accountability or skin in the game for an executive if they aren’t around to deal with the consequences of their decisions? Additionally, each executive typically has their direction or interest in how things should run. This means the organization thrashes from losing institutional knowledge and disrupting long-term projects.

These decision-makers typically don’t have enough skin in the game. In publicly traded companies, leaders frequently get stock options as long-term incentives. However, even without stock compensation, they are generally the highest-paid people at that company. They have enough money in their salaries that the impact won’t affect their ability to live.

Stock options as compensation for executives only work if they significantly negatively impact their well-being. For example, if their regular salary was a company average or median (depending on pay variation) of the rest of the company’s workers and their stock options don’t vest until after 7 years of employment, the long-term decisions they make may impact them. It is unclear what would be successful, but the decrease in retention and the lack of accountability means they make decisions that affect others without skin in the game. In some ways, the current pay setup for executives is like a gambler who gets to collect their winnings after they bet but before the game is played.

Contracts

At face value, contracts should create a skin in the game for both parties. A contract typically has penalties and rewards for a mutually agreed-upon set of deliverables. However, anyone who has worked in software creation or implementation knows we don’t know what good looks like at the beginning of each project. Software is often mistaken for a simple problem that is easy to implement. I wrote an article comparing this common fallacy, thinking software is a toaster when it is an unknown animal you bring into your company.

This means neither person in the contract knows what an excellent end state looks like. As a result, there is no skin in the game (for either party) to get the best outcome for the company or the shareholders, only to satisfy the contract. This also breaks the “If you Dev it, you Ops it.” rule. If the implementers aren’t around to support their implementation, then much like a 30-day warranty, they only have to meet the bare minimum of quality. This is a well-known industry problem, yet if the definition of insane is that we repeat the same mistakes repeatedly, we are an insane industry.

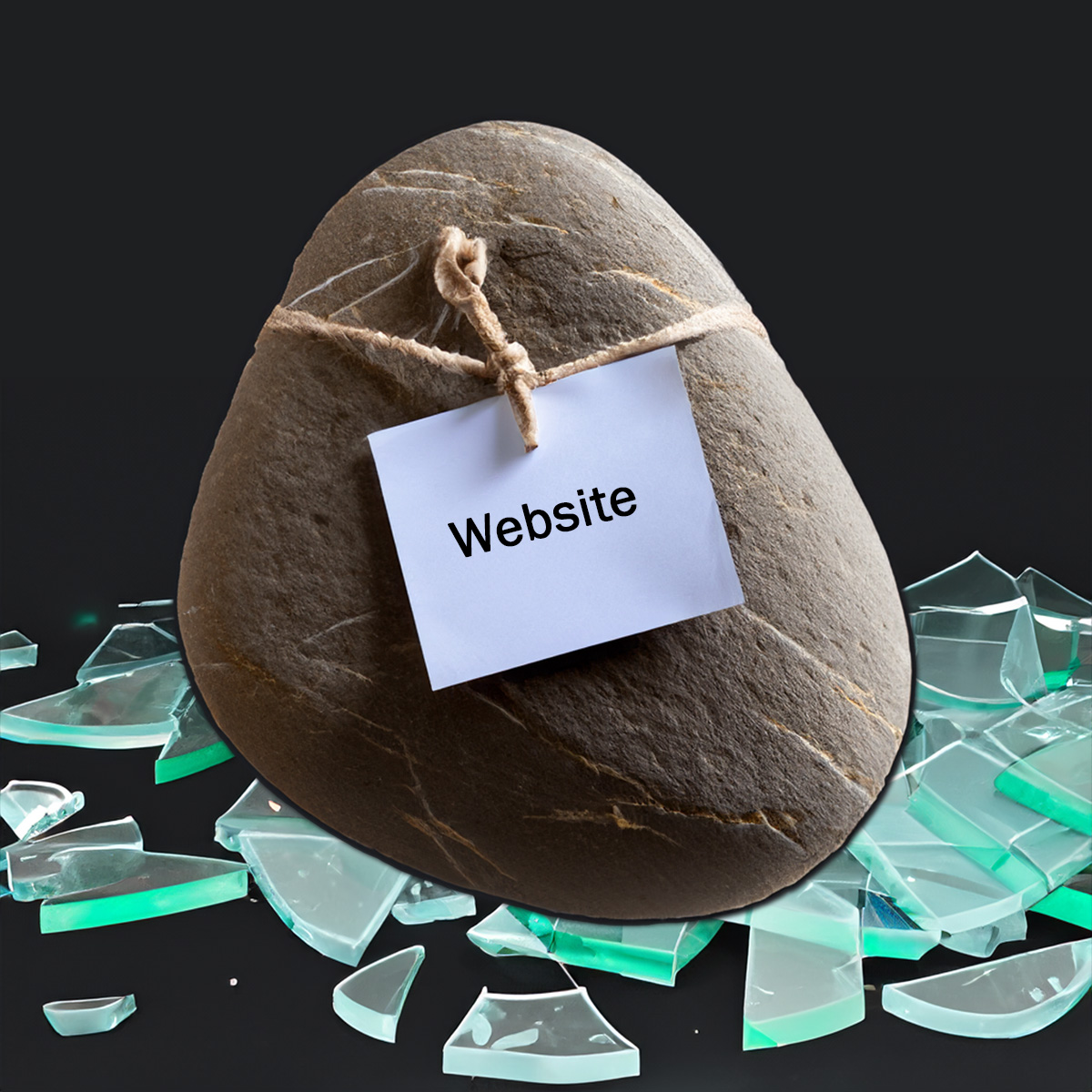

What if instead of writing a contract based on output, you write it regarding business outcomes? Imagine a clause in a contract, “The firm agrees to pay you for the development of the website/app when it has increased sales by 25% based on the baseline of revenue calculated EOY 2023.” When you start a new project, you never build software and put it on a shelf. It is supposed to create value. Unfortunately, lots of developed software is about as valuable as a rock.

The point of having a better website is to increase sales, the number of returning customers, leads, etc. Having one without delivering on the business outcome is a waste.

Users

I’ve mentioned developers, leaders, and contracts. The last major component is customers. I have been in product management/strategy for the past eight years, and one of the most common mistakes I see is for internal IT product owners thinking they can ignore user preferences because customers “have to” use their product. This could be true for a company that has a monopoly as well. The reality is customers never have to use your product. Here is a test, “How many users ask for a feature to import/export the data into an Excel spreadsheet?” When this feature is NEEDED, customers are trying to get a workaround for your “product.” Sure, there are use cases for analytics, but why is your user doing the extra work? If multiple users do analytics differently, they will make different decisions. Designing a product so its users proactively choose it, not figure a way around using it, is the key to a successful product.

Many large tech companies have made users feel skin-in-the-game when using their products based on how each product connects to the other and integrates with their eco-system. Eco-system-based companies are trying to create cross-product synergies to increase the skin in the game so that the user will keep choosing their product.

AI

As we move into a world where AI does more and more, it is starting to do more and more without human intervention. Last year, I wrote an article about trusting AI. The real reason we shouldn’t trust AI is that it has no skin in the game. If a Generative Artificial intelligence (GAI) bot quotes a price too low for airline tickets, it isn’t fired, but the company is still on the hook for the loss.

We do our job partly because we need the money to live. We have a lot invested in not doing something wrong for our company. AI doesn’t have this need. It doesn’t have any needs, which is probably good for humanity’s sake. It does, however, bring caution to who we let use AI and what we let AI do. Part of what we have been doing is limiting what AI responds with because it can, at best, send humans on a wild goose change and, at worst, cause financial or physical harm.

AI aims to satisfy the prompter rather than create an honest answer. The problem is that, to the uneducated, it looks correct. When it produces code that will run, it will sound like an answer when it answers a user’s question. The prompter will be held accountable for what it creates, not the AI. I wonder if we ever want AI to have skin in the game.

Leave a comment