Overview

Since college, I have found immense value in Robert Cialdini’s book Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion. I revisit it regularly, as Cialdini consistently updates it with fresh stories, analogies, and psychological insights. This is a must-read for business, marketing, and product design professionals, as it comprehensively explains the various strategies used to influence our behavior.

If you design products, you should be familiar with these levers because you may want to use them when creating your product. At a high level, there are seven levers described in the book:

- Reciprocation – When given something, you feel obligated to give it back.

- Liking – If you like the person, you are more likely to agree with what they are saying.

- Social Proof – We look at how others act to validate our actions.

- Commitment & Consistency – We prefer to stay consistent with our commitment. Small initial commitments make us much more likely to commit to bigger ones in the future.

- Authority – People follow the lead of experts and those in charge.

- Scarcity—What is limited and hard to get makes an item more desirable, especially when it was previously available and the supply is now reduced.

- Unity – We agree with and have a preference for people who are part of our group. This was recently added to the book and highlights the impacts of tribalism in our decision-making.

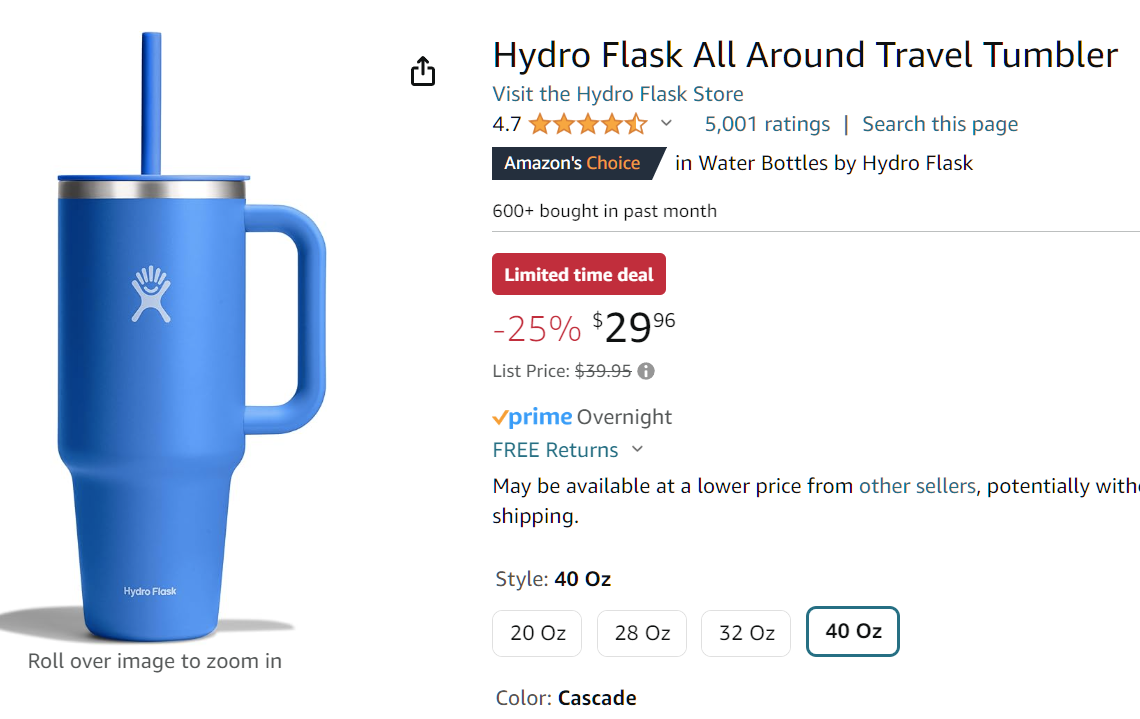

To best illustrate these, let’s use a quick example from a page from Amazon and see how many uses of these levers you can find on this one product page.

- Authority – “Amazon’s Choice.” This is similar to a story in the book about a Chef’s Choice being on a restaurant menu, which drives sales of that item. The expert has told us what is good, and we naturally assume the seller knows, so we pick what they ask us to choose. Authority is a powerful influencer to the point where, simply by wearing the proper uniform and claiming to be in charge, we have power. This power is more profound than ordering items, as the Milgram experiment demonstrates that people will harm or kill others based on what an authority figure in a uniform tells people to do.

- Social Proof—This page has many social proof indicators: 600+ bought in the past month, plus 5,001 ratings. People like this mug, and they buy it. Netflix does this as well, and other video streamers have copied it. The list of the top 10 most-watched shows has increased the number of people watching Netflix. An example from the book showed when customers at McDonald’s were offered a McFlurry, saying it was a customer favorite, sales jumped 55%

- Scarcity—This tumbler used to be expensive. The list price is 39.95, but there is a limited-time deal that gets us 75% off. In one experiment mentioned in the book, test subjects tasted and tested cookies. In one case, they stopped before the test started and took away most of the cookies, leaving only one or two cookies, saying they didn’t have enough for all test subjects. The study revealed the more scarce the cookies were, the better the test subjects rated the flavor of the cookies and were willing to spend more on them.

These are things that are not on the screenshot but frequently on Amazon.

- Consistency: Frequently, Amazon displays a list of items based on your past purchases calling them “items you’ll like based on past purchases”. This is a subtle influence of commitment: You bought this before, so don’t you want to repurchase it? This doesn’t sound big, but one of the tenets of commitment & consistency is you “start small and build” toward more significant and larger commitments.

- Reciprocity: You bought XYZ in the past, so we offer you a 10% discount coupon. They are giving me something; shouldn’t you use it? You can also get a “free shipping gift” if you spend $49 or same-day shipping if you spend $25. The example of reciprocity in the book that stuck with me occurred in a candy shop. When given a free piece of candy on the way into the store, customers were 42% more likely to purchase. Even if you don’t use the coupon, you’ve been given something and are more likely to buy something from the store.

Design Influence

As consumers, we must remember these levers are being used on us. As designers, we can carefully implement them or suffer a failure of a product that doesn’t interest our customers. For example, if you are creating a luxury product, it is essential to remember to have it out of stock most of the time. Matching production with market demand for fashionable products is a mistake, as demand is driven by scarcity and the consistency that valuable things are rare. Why are there still lines in front of the Apple store for the new iPhone/iPad?

The book covers many of these examples, but one way to use the influence levers is as a framework and then apply it to product design. However, these same levers are being used on designers as we make decisions about our products. Here are a few examples of how designers may be influenced during product creation:

- Reciprocation:

- A supplier takes you to lunch, and you feel you need to use their product. Or a company has previously paid you as a contractor and wants you to use their services in future designs.

- Liking:

- A friend or teammate recommends a feature they think is an excellent idea for your product.

- Social Proof:

- Everyone in the industry is adding something to their product, such as AI; we should do that because it adds value to that other product.

- Commitment & Consistency:

- We had something on our roadmap that we are starting to get evidence that may not be beneficial, but we told everyone we would deliver it. This is also another warning sign that roadmaps with too much detail are dangerous to your customers and you.

- Authority:

- The manager or architect told us to add this new feature or a new design element, XYZ. A recent Gartner report by experts said that all the growth companies are doing it.

- Scarcity:

- This may be our only opportunity to get this licensing, compute, color, or have resources to do x.

- Unity:

- On a long-lived team, this is where groupthink starts to seep in. “We all think this is a great idea.” This is dangerous because frequently, “We” does not include the customers.

Organizational influence

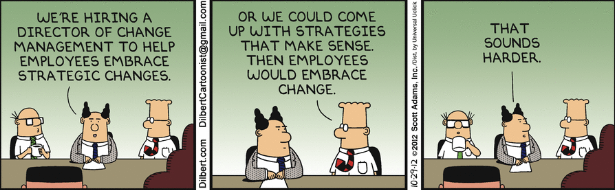

Thinking about other problems we can use this framework on, let’s apply it to enacting change within a large organization. What influences are preventing desired change from happening in your company?

- Reciprocation:

- Typically, changes in process, procedures, and how things are done come with a mandate. Yet, often there is no reward for doing the new thing. At best, there is a punishment. What are the individual’s incentives for changing?

- Liking:

- We like things that are familiar to us, and change is the opposite of that. In the book Influence, the author gives an example of taking a selfie and reversing the image. Print both the original and the reverse. You will like the inverse one because it looks like you are in the mirror, but your friend will prefer the non-reversed image because that is how you look in the regular world.

- Social Proof:

- Are other similar companies changing how you want to move your company? Once all the other companies adopt the most popular software, process, vendor, etc., it is far easier to get adoption inside your company.

- Commitment & Consistency:

- Many people have worked hard to do things as they have been. They also have been rewarded for doing them that way. This years of reinforcement to keep things the way they are.

- Authority:

- If leadership doesn’t want change, it won’t happen. It is difficult for long-serving leaders to participate in change because of the commitment and consistency from above.

- Scarcity:

- New processes, software, and ways of doing things are a dime a dozen. Why try this new one out? How can it be worth anything?

- Unity:

- “We have always done it this way.” When someone says this, they are saying that their identity is attached to the way things are done. It is not that we have been doing it, but rather that they are saying “WE” when describing it.

What are ways to make a change in an organization possible?

Knowing the levers of influence, here are some ideas to ensure buy-in to organizational change.

- Authority: Get leadership buy-in. When the authority says to do something, especially at a company, people will do it. Look for informal leaders as well. These organizational experts have a lot of sway, and formal leaders frequently look to them for confirmation.

- Commitment: Implement small changes first. Once someone commits to any change, they will commit to more significant changes later. Small commitments and change get the ball rolling.

- Reciprocation: Those who adhere to the changes are championed in emails or video updates from leaders. Those who are recognized and rewarded for small commitments to change get something personal out of it. Not only are they likely to change again, but others will also want to. It is even better if someone publicly gets an award for their commitment to the change.

- Scarcity + Liking + Social Proof: Don’t allow all groups to participate in the change; this creates scarcity. It is even better if it is done by a well-liked group; this gets the “liking” and “social proof” levers pulled. Ex. “Our engineering team said they enjoyed their work more after making this change. Increasing their job satisfaction scores by 80%”

- Liking: Include information about the change in all regular communications. Overcommunicating a message removes its unfamiliarity and increases people’s liking of it. This makes change expected and not atypical. Factory organizations that don’t like specification variation may struggle with the concept of change and variety. Getting them to like and embrace change will take time.

- Unity: Facilitate ideas of change from within the organization. Share success stories from within the organization, which taps into social proof and unity. A common mistake is showing how a competitor made the change successfully; this will likely build resistance, not a commitment, as a competitor is a “them” group, not an “us” group.

Understanding Robert Cialdini’s book Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion can help any human endeavor. We need to know how we are being influenced and how to influence others effectively. We also need to understand how misunderstanding these forms of influence can cause our endeavors to fail.

Leave a comment