Summary:

- Most people know time is money but we don’t always act that way. Frequently we ignore the time value of money when evaluating a project and if we do, we build hidden costs and lose opportunities.

- For high-value projects, development costs are typically the least important metric but the easiest to calculate. The ease of calculating a metric makes it tempting to make the development costs the total cost of a project.

- Learning what the customer needs is always an iterative process. Most contracts do not allow for continual discovery. This leads to at best suboptimal solutions and at worse a total loss.

A parable:

In 2010 the Affordable Care Act (ACA), sometimes referred to as Obamacare passed congress. States were responsible for determining how their citizens would be able to sign up for a subsidized healthcare plan. Oregon chose to make its own website, Cover Oregon. To build the website they hired Oracle as a consultant.

It was supposed to go live in mid-October 2013 to help provide time for the mandatory enrollment by mid-December. At this point in October 2013, the state had spent $160 million dollars and had not been able to process a single applicant. The state had to switch to paper enrollment and then by April 2014, the state of Oregon switched to the federal website Healthcare.gov and scrapped the whole project.

A lengthy legal battle ensued between the state and Oracle. Where each side claimed they were wronged. Oracle wanted to get paid the full amount of the contract and was claiming that the state didn’t provide clear enough requirements. The state ultimately settled with Oracle, in 2016, for an additional $35 million in cash payments and $60 million in software and service fees for the next six years. Though the state was able to recoup $20 million in legal fees.

This is a very public example of what happens in large-scale big bang projects, but not all of them make it into the news. Hertz is suing Accenture for $32 million, claiming they failed to build them a phone app. With legal fees approaching $20 million, how many more disputes don’t make it into court?

Feedback not contracts

According to a CNBC report, “state officials were unable to define requirements for the Cover Oregon system, an essential early step, and even went on a 60-day ‘retreat’ to develop them but ‘returned empty-handed.’” Even if they had a great plan it wouldn’t have worked, users, and not great ideas dictate success. The discovery process for a software product is diametrically opposed to the requirements upfront process. How can we make a recipe if we don’t know what we are cooking? Many projects think they have a great plan until it gets shown to the user.

Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.

– Mike Tyson

Yet most contracts ask us to determine the outcome when we have the least amount of information, at the beginning before we get punched in the mouth. The feedback from users throughout the process is the information we need to make the product more usable and profitable. How much more profitable?

Let’s do some calculations to find out.

Whenever looking at a potential investment, we calculate the cash flow that we would make when it is released. We have to account for the development costs so we subtract those from the future cash flow. Since we have an expected return on our money, we will need a rate (i) for what we expect to earn. The calculated total is the net present value (NPV) of our potential project.

In looking at this calculation, the time value of money is included for both our perceived cash flow and the development costs. Time is one of the biggest factors in making a profit and luckily we have a lot of control over that variable. By examining some different scenarios let’s see how time impacts profitability. For example, if the project is completed in 6 months the NPV is can be very different than if we complete it in 18 months.

Scenarios

Let’s make up a software project we want to deliver for a large company. There is an opportunity to make/save $24 million dollars if we deliver some new functionality. To simplify this I will use a single number for cash flow in our scenarios and skip opportunity estimation, but if you want a book that provides those details on how to do that I highly recommend How to Measure Anything by Douglas Hubbard.

Our required rate of return (i) is 33% or 2.75% per month, on our time scale i=2.75%. Let’s further assume we have 2 opportunities for development. We can choose a team of six highly skilled software engineers at $350k a piece for a total of $2.1 million, or a contracting firm offering us a $180k six-month contract.

Depending on when our project is done (t) we can compare the various NPVs we can expect.

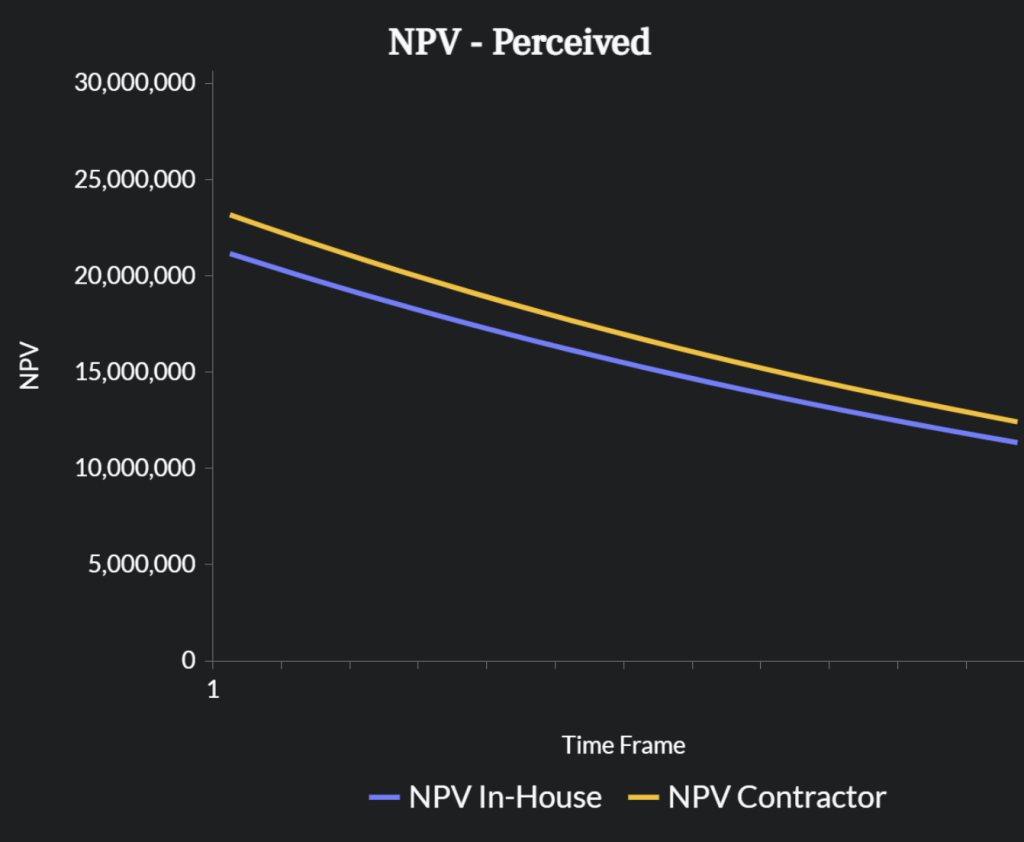

Scenario 1: Straight Forward

The yellow line is always above the blue one at every time interval. The higher NPV is the one we should pick, which is the contractor. Done deal, right?

This comparison assumes that both the contractor and our in-house development team will be done at the same time. For a more realistic comparison, we need to factor in a few things about dealing with a contractor and contracts. These factors can add cost and time:

- Negotiation – New contracts take a long time to set up. Even if you have an established provider, there is additional work and negotiation that needs to happen, like creating a statement of work, finding resources, legal review, etc. This adds to our timeline which impacts our value.

- Output-Based Contract – Output-based contracts ensure that teams produce a certain level of output, which is maximizing utilization of resources which is usually maximizing waste. The Oracle contractors did a lot of work, but it didn’t achieve what the state needed. In the end, Oracle still got hundreds of millions of dollars. These contracts not only add to time but may drop the overall value in our calculation to zero, as it did with Oregon.

- Outcome-Based Contract – There are two big problems with outcome-based contracts: 1. They tend to cost a significant amount more. 2. You probably don’t have the right outcome at the beginning because no one is good at defining upfront requirements. You could blame State of Oregon officials but realize they were asked to design requirements for a website based on a brand new law and process no one had gone through yet, even on paper.

- No skin in the game – If you have an output-based contract what is the incentive to be more efficient and effective? The longer you take the more you get paid. If you have an outcome-based contract you may want to be more efficient but you have a legal obligation to be less adaptable unless it is written into the contract. Changes to the outcome lead to more negotiation and a new contract. This adds to the timeline.

Not all contractors are bad, some are really good but those are rarely cheap (not that cost is a sign of quality). In some fields, contractors are 100% required, in a lawsuit you may need to hire a firm to do digital forensic data collection. Hopefully, you’re not always being sued and it makes little sense to keep a set of developers on staff for that kind of work. Other scenarios include auditors, educators, or new technical skill acquisition.

But in general, even with big-name contract firms, they take at least twice as much time to complete a project as an in-house team. I don’t want to get into any legal trouble so I won’t name names but I anecdotally have seen the following delay tactics:

- A contracting firm can provide a resource, and have them spun up and trained, only to replace them two weeks later and the process starts over again, delaying the project. More money for them.

- A contracting firm can suggest improvements to the project, pausing the process to get several partners together to discuss their improvements. A week later we meet to discuss their brilliant ideas, only to discover they are simple non-value add ideas. More money for them.

- A contracting firm can suggest they can provide a better contract with your software vendor if you let them handle it. There are savings but you find out that if you drop the contracting firm, then you lose your software licenses. More money for them.

- A contracting firm will insist on using a technology that they are experts in but isn’t at your company. The expertise lies with them and you have to spin up your staff on the new technology. More money for them

If you are relying on contractors to completely build a software product (app, website, or IT implementation) because you don’t have that expertise, then you better have expertise in contract law.

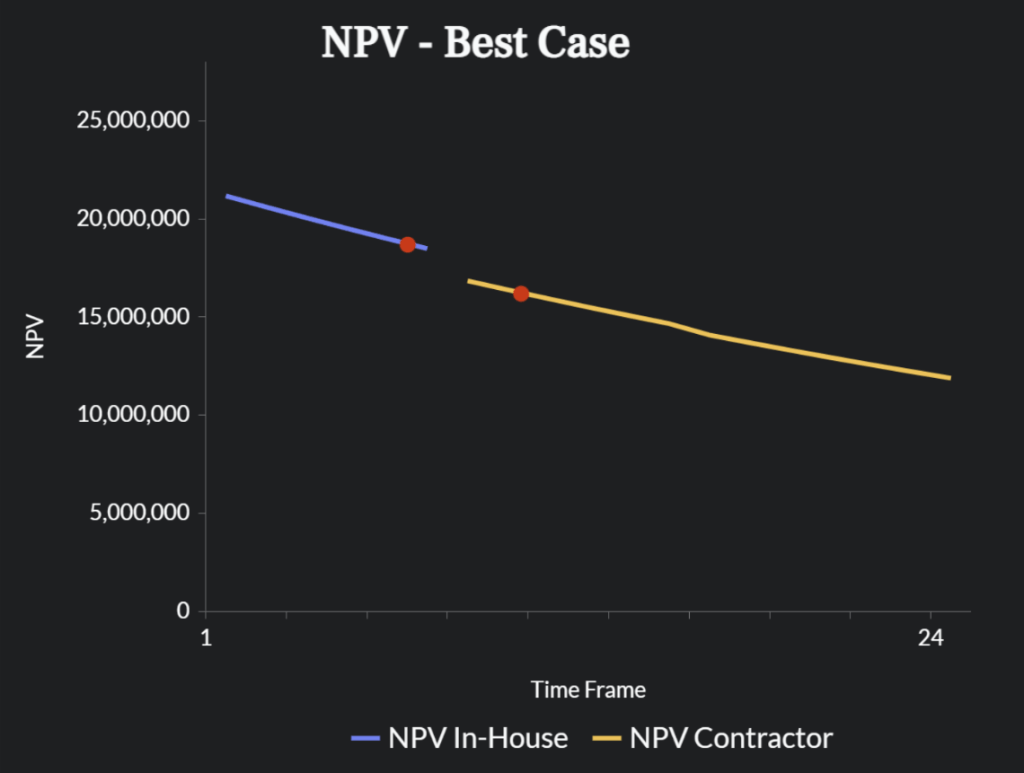

Scenario 2: Best-Case

Going back to our example, let’s give our imagined contractor the best-case scenario and factor in the delays outlined above. Giving them the benefit of the doubt, they take twice as long but still deliver what was needed. In that case, our NPV looks like this.

Instead of comparing the two lines, compare the two points. The red dots are the most likely time interval of delivery. The lines themselves are the variance of possible delivery times. Notice that the NPV of the earliest possible delivery date for our contractor is still significantly less than the latest of our in-house experts.

By spending more on the in-house team we made at least $1.6 million more than waiting it out with our contractors. Not only that but our in-house team could already be working on the next $20+ million dollar idea.

Scenario 3: Market Fit

As mentioned in my previous article about Market Fit Debt, there is always a gap between what we release and what is really needed. Let’s visualize that:

The value of our idea when we release it to the market is actually half of our initial projection. As a result, NPV is adjusted down. The in-house team can adapt because we understand the market better upon release, and we have an opportunity for the product to be adjusted for a better market opportunity. However, with our contractor, our contract is done. What is highlighted here is that there is more ability to adapt to the market with dedicated in-house resources. If you are working with contractors, you’ll need to account for the continual learning and changes to fit the market.

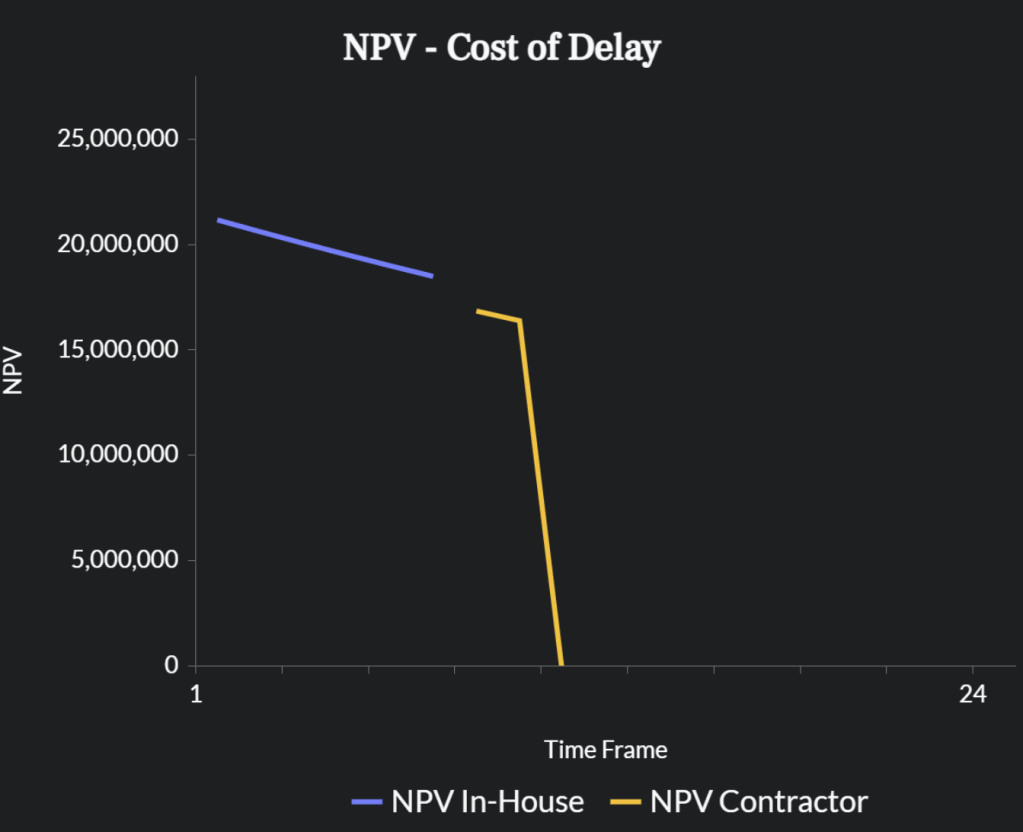

Scenario 4: Cost of Delay

None of these scenarios assumes a competitive market. Normally everyone has competition. That means we have a delivery window to get something into the market or we start impacting the cash flow projections. This is another area where Hubbard’s technique can come in handy as you can start to figure out what are the greatest drivers for impact to value.

This delay of delivery and the impact it has on cash flow projections is frequently referred to as, the “Cost of Delay”. This means we miss timing the market and as a result, we make significantly less. We could be selling at a loss just to get back some of our initial investment. A more likely scenario in a competitive market looks like this:

This scenario is probably the scariest. It visualizes the old saying, “You snooze you lose”. It is all too real in today’s fast-moving markets. While contractors can slow you down, they aren’t the only thing that can delay a project and potentially cost you a fortune.

Delay to Feedback Impact the Top & Bottom Line

Frequently delays are the difference between making or losing money. The more feedback loops we need to get something right, the contractor becomes a worse choice. A delay can be caused by things other than a contractor. Here are some common delays:

- Lack of access to the customer

- Go-betweens

- Program teams spread across the world

- Team members spread across the world

- Ticketing systems

- Technical review boards

- Any wait states.

In our example, a single-day delay of $1 billion project costs $903,292. Suddenly bringing the team together to get something done in 2 weeks instead of 10 weeks starts to make more sense. One reason start-ups are so successful is that they have all the people needed in the same room, or at least they are all within the same time zone.

Hidden Costs

There is a hidden cost when using contractors exclusively, which is a loss of knowledge. Learning happens in the feedback loops as we ideate on a product. Back when I started this site the first thing I wrote about was how to become an expert. The core of the learning process is trial and error with feedback loops. In any project, you are creating experts in your business systems. How it works, decisions that were made, tweaks to the original specification, and really how your business runs. When only using contractors that expertise leaves when they do, this is knowledge debt. We are making implicit choices on our company’s vertical integration because with each contract knowledge is no longer in our company.

Rational

Time is money is not a new concept. Missing market opportunity isn’t a new concept either. How does this happen? One reason I’ve seen for this is that development cost is a concrete measurement, and we are held accountable for the cost which is easily measured and potential revenue is not. Lost potential revenue never happened, so it can be hidden. Additionally, when a better alternative was ignored, we ignore all the potential lost revenue that went with it. If a contract failed then it was a problem with the contract or the contractor, but a loss in potential revenue isn’t captured.

We don’t live in a timeline where we achieved the best outcome, this may be the worst timeline.

- These costs aren’t hidden in the marketplace. If we are losing in the marketplace, then there is something suboptimal in our product discovery and delivery system.

- If our systems don’t satisfy the needs of running our business, then those hidden costs are in the form of technical debt. How much of your business runs in excel spreadsheets and not in its IT systems?

Final Thoughts

Once a project starts it is rare to track how the projected value is changing, but it doesn’t mean that it is static. While the value may not be as concrete as development costs, it is still impacting your business. If there was value in the market and you didn’t capture it, then you leave that for your competitors to get.

Measuring and tracking the time value of money and making it part of your decisions can help reduce that impact. If the value of a project is known then decisions about the speed of delivery become easier to make. If the value of your project is $1 billion, then it may be worth it to fly everyone onsite, pay for hotel rooms for them, and even fly their families there to keep them happy. Anything to keep the timelines as short as possible. Of course, if the value of a project is only $100,000 then you probably care quite a bit less about delays.

When looking at the system of delivery, I look at it like a factory. Where is there waste? Delays, hand-offs, work in progress, negotiation, or delivery without learning. Contractors are a good scapegoat for these because they tend to profit off your waste. They are incentivized to create more of it. Whenever I map a workflow I include wait times and how often those occur. The cost of 5-minute tasks that can take 7 days to get worked on can be shocking. This is important because you may think, “Why would you want to automate a 5-minute task?” But if that task is done in every project at a company, and the cumulative value of all projects in that company is $1 billion, then that’s $6.3 million that can be saved every year.

Leave a reply to Jason Amici Cancel reply